Susan Else grew up in a family of artists. She got bored with flat quilted surfaces and started adding three-dimensional elements. Now she creates 3D fiber art using a variety of armatures. Each piece has a story to tell.

How did you find yourself on an artist’s path? Always there? Lightbulb moment? Dragged kicking and screaming? Evolving? Tell us more about how your work evolved over the years to now creating textile sculptures.

I grew up in a family of artists, but was determined never to become one, and in fact I pursued a 20-year career as a writer and editor. (I mean, what self-respecting teenager wants to follow in her parents’ footsteps?)

I had always been interested in textiles, however; they were on the other side of the art/craft divide and thus no competition with the painters, sculptors, and filmmakers in my family.

I learned to weave before I was 20, but eventually I got bored with the warp/weft grid. Quilting was more flexible, even when pursued in a traditional style.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Read more about our affiliate linking policy.

After about 10 years of “hobby quilting,” I began to take the art potential of the medium seriously. Nancy Crow’s book Quilts and Influences showed me that one could make a serious life and career in quilting.

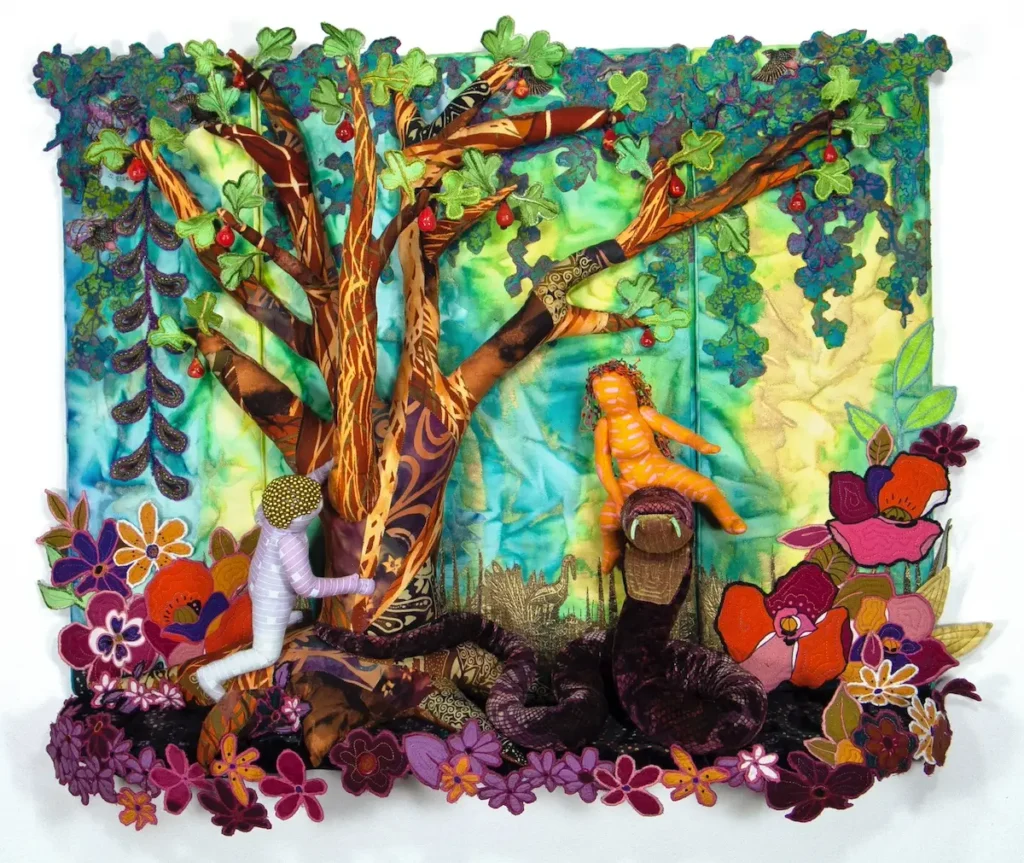

Eventually I got bored with the flat quilted surface and began adding three-dimensional elements, including figures. After breaking the essential rule of traditional quilting (“It must be flat!”), I was free to innovate in any way I wanted. Soon, my shallow dioramas migrated off the wall and became fully three-dimensional.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received?

I had plenty of experience living with people who were artists, so once I dropped my resistance to being one, it was an easy role for me to step into.

I don’t remember any particular “advice” I heard along the way, but growing up with people who made art was crucial. I had a pretty realistic picture of the rollercoaster of tedium and exhilaration that I was signing up for!

Does your work have stories to tell?

My realization that I was in fact making art gelled after I starting working with cloth figures. On my design wall, my first crude figures immediately came to life as part of a narrative, interacting with each other and with elements around them (even if that narrative was deliberately ambiguous). It’s hard to tell visual stories and then say it isn’t art.

Although my 3D work has always reflected aspects of my own life, in the beginning I was on a voyage of discovery to see just what I could make: how many aspects of the physical world could I represent convincingly in fabric?

I was thrilled when people couldn’t believe my work was actually made of cloth. As time went on, what I had to say about the world became more important than just being able to depict it.

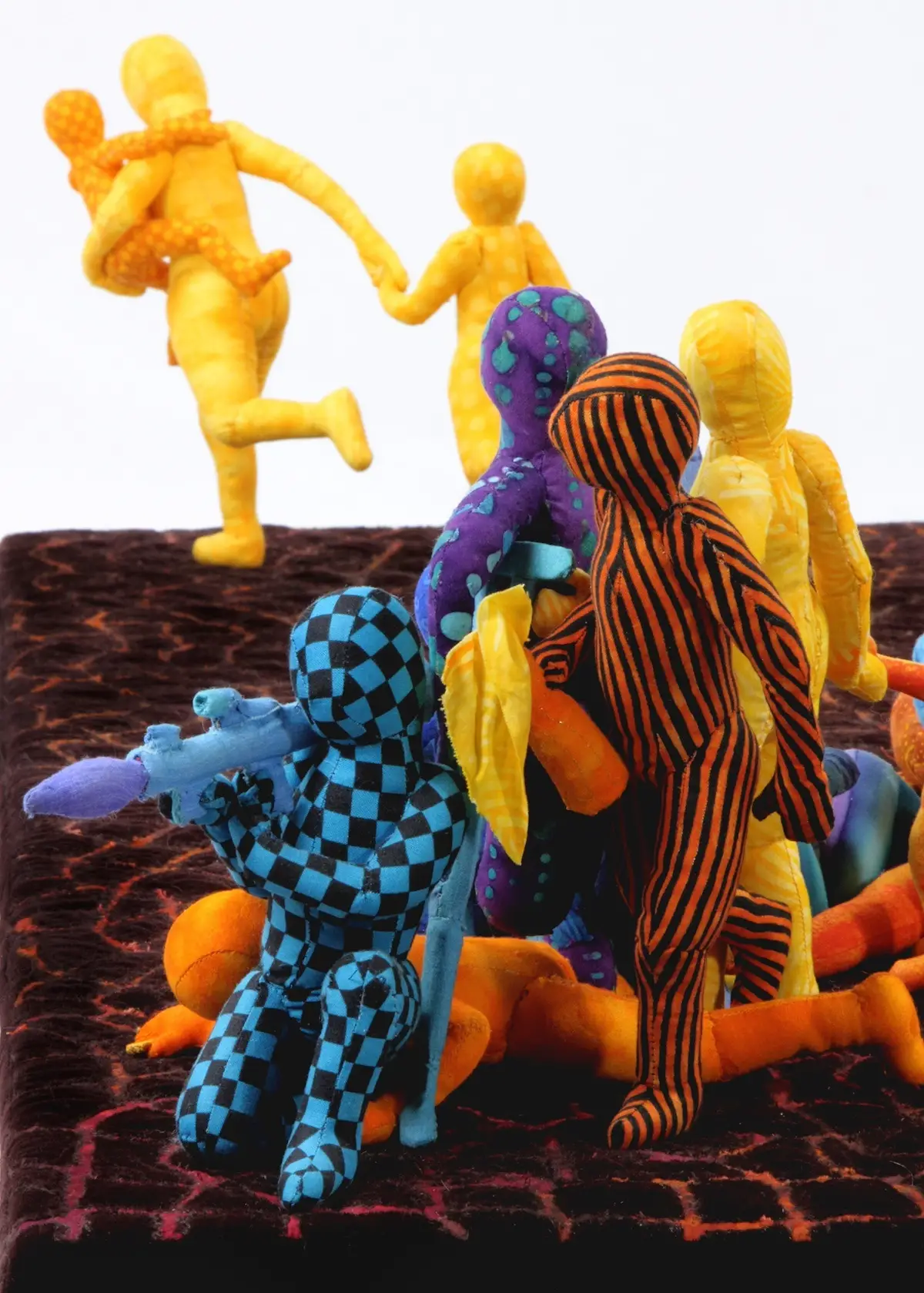

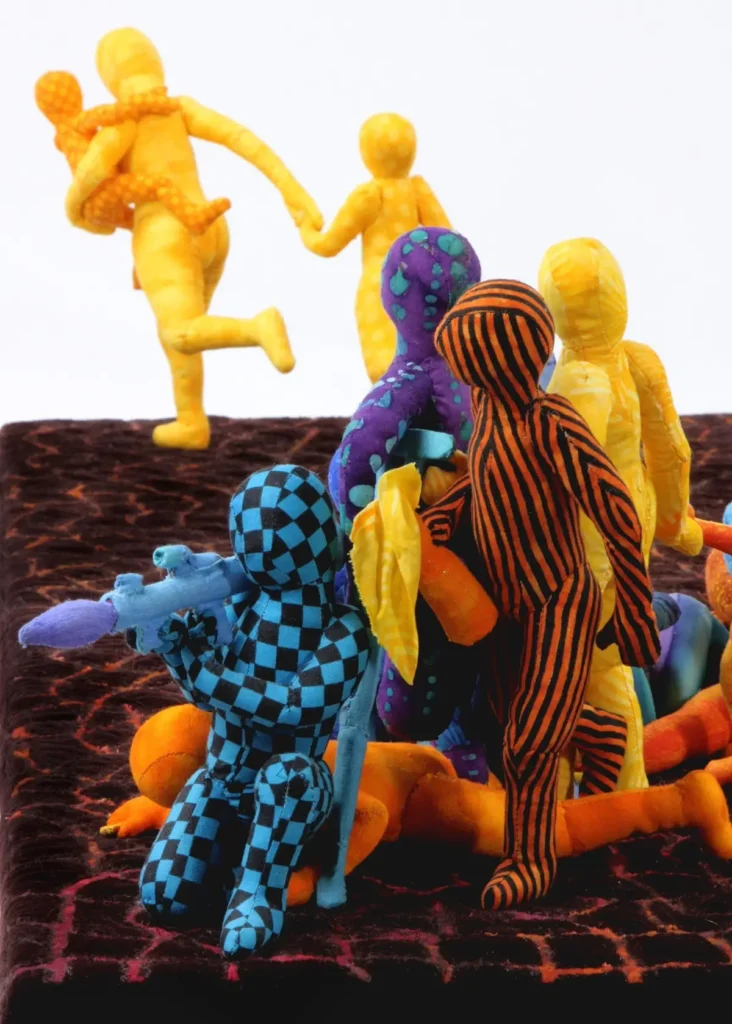

Although they have included a strain of wry whimsy from the beginning, my narratives have darkened along with the world itself. I often call my output “stealth art:” the cheerful color and comfortable ambiance of sewn cloth draws viewers into the work, where they are often confronted by a more nuanced and disturbing picture of the world.

But my delight in the medium is always evident. My best work fuses contradictory human impulses into a single image, leaving the viewer with multiple responses.

How does working in a series affect your approach?

My work can be organized into major series:

– Figurative dioramas: usually involving social commentary,

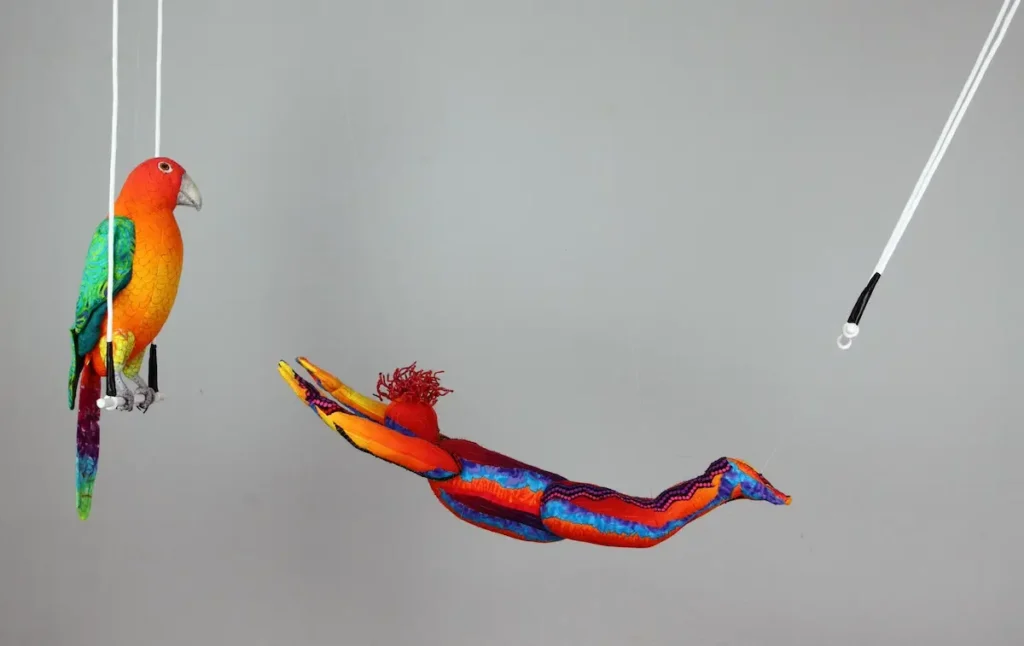

– Without a Net: a ten-piece exploration of the old-fashioned circus and sideshow, incorporating motors, lights, and sound. Here is a video that describes the Without a Net series: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KOa0ynVh4Bs

– Mortality: gestural skeletons in benign poses,

– Heirlooms: human artifacts (especially domestic items like chairs and bowls) made of cloth-covered bones,

– Still Kicking: because sewing against hard armatures has become difficult for my aging hands, this recent body of work involves simpler figures, often fierce old women.

Often I didn’t realize I was working in a series until I’d done a few pieces with a similar theme, and then I would add pieces to the series as long as it held my interest.

Now I’m a little more intentional about the process, as in, “I seem to be making grumpy old women with mobility issues. I wonder how many versions of this are viable?”

I don’t work on a single series at a time. They overlap and lead from one to another, and I may revert to old themes years later. Sometimes it takes preparing a lecture about my work to see the series progression. Right now I seem to be making boats.

Where can people see your work?

All of the series can be seen on my website, while current work-in-progress tends to show up more quickly on Instagram and Facebook. My work can also be seen in major art-quilt shows (https://dairybarn.org/quiltnational/), on the Studio Art Quilt Associates website (www.saqa.com), and in articles like this.

Website: www.susanelse.com

Instagram: susan.else

Facebook: Susan Else

Do you plan your work out ahead of time, or do you just dive in with your materials and start playing? How often do you start a new project? Do you work actively on more than one project at a time?

I don’t draw well, so I don’t usually sketch out work before I do it. Unless a commission requires sketches, I just cut and go.

I usually start a piece with a vague idea of what I want to represent. I make one element, and when that is successful, I add more components. Because my work has so many visible sides, it takes forever to finish, so my output over the years has been limited.

If I get stuck and have the luxury of time, I will work on more than one piece at a time, but one piece is usually the focus of the studio—along with the non-glamorous administrative grind that goes into being an artist.

What techniques are used to create your sculptures?

My bigger figures have a collaged and quilted surface, and often I try to make the collage relate to the narrative—even if there isn’t a literal connection. Smaller figures need a simpler and more unified surface; I construct each of these from a single fabric.

I use machine-collage techniques, with invisible zigzag stitches, to construct the surface. Typically, I will cut up that collage, quilt the parts, and then machine-sew the pieces together (imagine making a teddy bear).

I use a doll-making tool called a stuffing fork to insert the polyester fiberfill that’s inside the figures (many are also reinforced with wire). But once an element is three-dimensional, you can’t use the machine any longer; the arms have to be sewn to the body by hand.

Once a body is constructed, it looks like a stick figure until I hand-sew all of the gestures. That’s what makes the figures believable. I avoid adding facial features, because they can be so static. I find viewers are better able to project themselves into a figure through gesture.

The fact that I often use bright, vividly patterned fabric gives the pieces a kind of serendipitous universality. It’s hard to assign an ethnicity to a figure made of green polka-dots.

I avoid idealized body shapes, and that also helps in reaching all kinds of viewers. One of the things I like about the skeleton series is that the gender of the figures is ambiguous, so the viewer has to focus on the human gesture instead.

For the bone work, I hand-sew a small quilted collage over each bone; I use bones from commercial plastic skeletons and pose them according to my narrative.

Skulls can’t possibly gaze tenderly at each other, but the gestures here convey that emotion. At the same time, the skeletons themselves remind us that life is finite.

Of course, I’ve had to learn how to construct the rest of the world, not just figures: plants, houses, washing machines, flags waving in the wind.

Each type of object necessitates different construction techniques—from applying the quilted surface to an underlying armature of wood, metal, or plastic, to couching wire onto fabric to give it strength while maintaining its thinness.

I avoid glue and rely on the permanence of my stitching instead.

Here bones evoke history, and this rocking chair calls to mind the activities of previous generations—and the ongoing human struggle to get children to go to sleep.

When the narrative requires it, I use technology in my work: motors, lights, and audio.

The first time I did this was with an oversized teapot with figures drinking tea inside. When I first exhibited the piece, viewers admired the outside but didn’t look inside.

I solved that by sewing rope light under the rim; the resulting shaft of light pulled viewers to explore the inner narrative. But I don’t incorporate technology unless I see a need for it; creating a world in cloth is my main motivation, not using blinky lights for their own sake.

Because my work often requires skills besides sewing and imagination, I have collaborated with other people over the years: woodworkers, metalworkers, audio engineers, and so forth.

Luckily, my husband is quite a fabricator, and he has helped my more complicated pieces achieve stability and functionality. I couldn’t have done this work without him. He’s also a wonderful photographer who shot all the images used in this article.

Scraps. Saver? Or be done with them?

I save scraps. My work is made up of small surfaces, so small bits of fabric can be useful.

However, I also think one of the things that forces you to grow as a textile artist is that lines of fabric disappear over time, so you have to reinvent what you’re doing in terms of what’s available at the moment. I use mostly commercial fabrics, combined with cloth hand-dyed by others.

Describe your creative space. What are the indispensable tools and materials in your studio?

I live in a Victorian house in coastal California, and my studio is in the old front parlor.

Despite its charm, the space was not built for a working artist, and at this point it also houses our guest bed. It’s small, but I do have a design wall and a big flexible sewing table, as well as open shelving for my fabric.

My armature materials and fiberfill are stuffed in a closet. I store thread, as well as needles, drills, stuffing forks, Xacto knives, saws, and pliers in the old typecase my mother used for storing her sculpture tools.

My desk, computer, and files are in the studio also, so on a good day I can move from administrative chores to making art.

What do you do to keep yourself motivated and interested in your work?

I wait out the dry times. It’s not a question of not being interested, just that being a figurative textile sculptor can be lonely and discouraging, and sometimes it’s hard to remember why one bothers.

Can you tell us about the inspiration and process of one of your works? How does a new work come about?

Dream Boat is my latest piece. I’ve made several boats over the course of my career, and I’m interested in the idea of a boat carrying a scene that the viewer does not expect. Contradictory elements fused, one more time!

I saw a big stack of ceramic boats a few months ago in someone else’s studio, and that reminded me about how much I like to work with them. They are so laden with meaning in and of themselves (exploration, risk, escape, movement, tranquility, etc.), and can be very complex when what they carry is a surprise.

So a person in a hammock in a tree in a boat seemed just like the kind of wistful mental get-away we all need right now. It was fun to make this; I started with the collaged boat exterior and moved on through the tree, hammock, and figure.

Interview posted July 2025

Browse through more inspirational sculptures on Create Whimsy.