Fiber artist Mita Giacomini creates powerful, intimate bird portraits using a technique she calls surface weaving. In this interview, she talks about discovering fiber later in life, breaking all the “rules,” and how time, texture, and close observation shape work that feels deeply alive.

Tell us about your journey as a fiber artist. Did you choose it, or did it choose you? Was there a defining moment or piece that revealed fiber as your medium?

Since early childhood I’ve loved both needlework, especially knitting, and artwork, especially drawing. I’ve always admired fibre art of all kinds but was in my forties before I understood that art and fibre could be woven together (so to speak) by ordinary people like me. I’ve only taken one fibre art class.

It was a single day of textile collage with the wonderful Maggie Vanderweit. First, she gave us each a pristine piece of canvas and had us tear holes in it (yikes). Then she gave us a generous, whirlwind introduction to surface design techniques. I most cherish her overall lesson that you can do anything with fibre to get artistic effects – including breaking all the usual needlework and sewing rules. Frayed edges, paint splashes, and torn holes are all beautifully expressive. After that one day with Maggie, I felt like a bird let out of a cage.

At first glance, my pieces strike some people as paintings, so I’m often asked why use fibre as a medium instead of paint.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Read more about our affiliate linking policy.

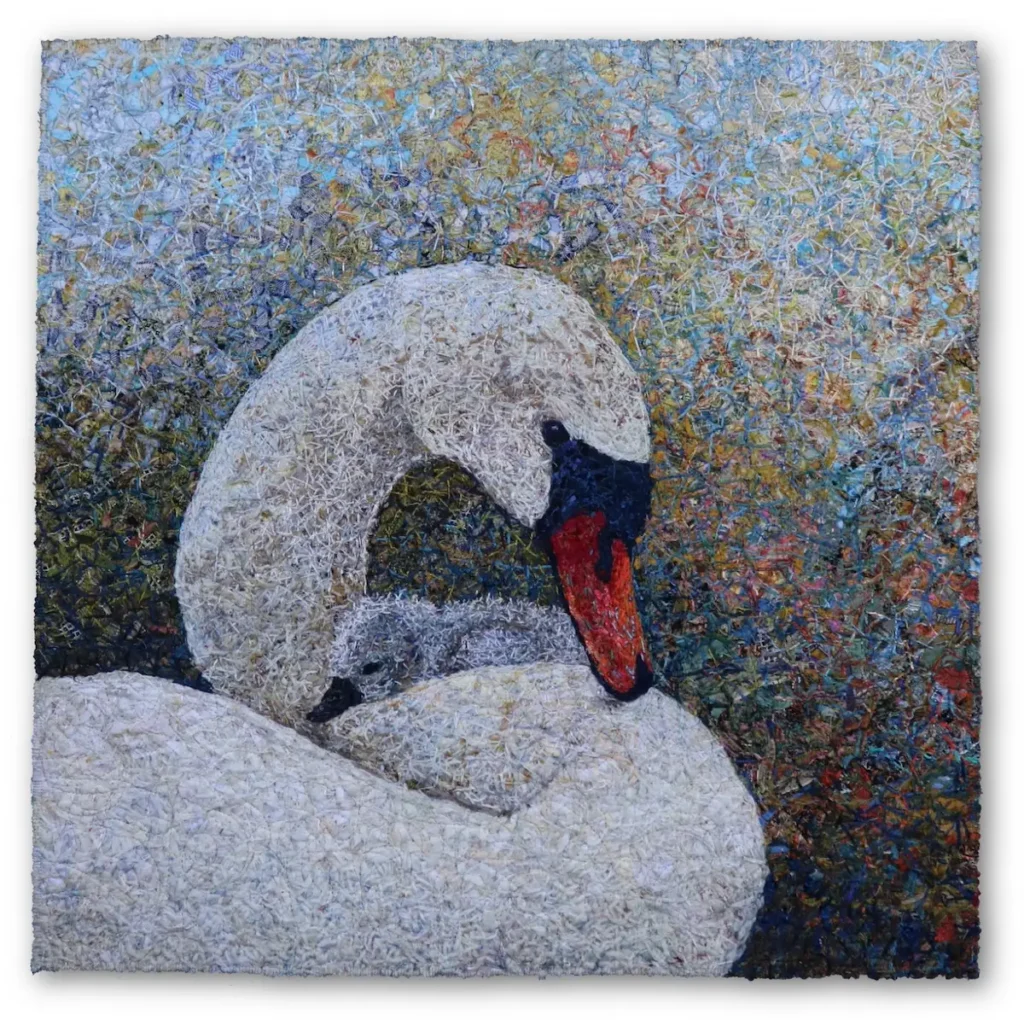

Fibre has unmatched expressive qualities. It’s so intricate — from its textured surface right down to the microscopic level of its filaments. This quality is common in nature, and I think people respond to that intuitively.

Fibre is also deeply meaningful. Countless creative people make the yarn, threads and textiles that we put into our pieces. Viewers recognize this, and it offers them more to savour visually. And of course, no two fibre artists work with the same supply of materials – we forage and collect wherever we’re situated. We don’t get our media from art supply stores. All of this is creatively compelling and different from the world of paint.

Describe your creative space. What does it look like? Organized chaos, zones for each type of work, or something else?

My studio is one room, filled floor to ceiling with baskets of materials and artworks in progress on design walls. It looks messy but it’s important for me to see the available fibres while I work.

When a painter wants a particular colour for her next stroke, she dabs her brush in the blobs of paint on her palette. When I want a particular color (texture, weight, pattern, etc.) for my next stitch, I go digging through my baskets for just the right strip of cloth or bit of yarn. This means the whole studio is an active, kind of chaotic workspace.

I cherish solitude. When I do have a visitor, I have to “disorganize” it to clear space for them to stand safely and to make sense of it all.

Do you have a favorite fiber or thread that you keep returning to?

I use primarily silk, wool, cotton, linen, and in various forms – textile strips, threads, strings, yarns.

I have the keenest feel for natural fibres, though I do also use some synthetics for particular effects.

I seek out upcycled materials — they’re ecological, and often especially meaningful. There’s also more variety, and often at better quality – for example, most exquisite silks used for designer neckties aren’t available at fabric stores.

I sometimes get very attached to a one-of-a-kind fibre. I have a spool of vintage rayon raffia that I’m guessing originally came from a long-ago commercial workshop for hats or handbags. There must be a bit of this in almost every piece I make. I wish I knew where to find more of it.

What essential tools and materials do you have close at hand? What couldn’t you work without?

I’ve collected so many different needles, bodkins, hooks and grippy-things suited to weaving different sorts of strands, but my main handweaving tool is a simple aluminum bent-tip tapestry needle.

My other indispensable tool is a ratty-looking quilting glove stuffed with various thimbles and with hockey tape stitched to the fingertips. It allows me to push and grip needles effectively.

Probably the biggest investment I’ve made in my studio is a small long-arm sewing machine, and it’s been worth every penny it cost and every inch of its footprint.

How do you balance technical precision with emotional and aesthetic spontaneity?

This is a great question! I often think about this – how each piece goes through many stages, fast and slow, spontaneous and methodical – and how different kinds of creativity and decision making come into play.

Early in the process come quick, spontaneous moments such as encountering a bird, noting observations, taking photos, and selecting images to use as studies.

Birds don’t keep still, so photos are a crucial reference. Slower, more technical stages involve working up studies to guide the weaving – working things like composition, colour gamut, the sources and play of light, etc.

One I’ve got that roughed out, the hand weaving stage is spontaneous and intuitive driven as I choose each individual strand and work its way through the emerging image.

I’m creating little serendipitous, abstract vignettes in each square inch of an otherwise realistic overall image. These handwork hours are really the most lyrical stage of the process. At the end, I aim a cooler eye at the piece and slow down to give it a good critique, looking for things that aren’t working to fix. Tidying up loose threads, so to speak.

Do mistakes ever become creative breakthroughs in your work?

My biggest mistake led to my invention of surface weaving, which has been my biggest breakthrough. I’d been intensively embroidering an art quilt with various weights of yarns, and the stitching was a slog, pushing a big needle with thick strands through the fabric. After several hours of exasperation, and sore hands, and I stood up to take a break — and found that in all the furious needle-jabbing I’d accidentally stitched part of the piece to my jeans.

That final straw made me put down needlework for a while, and ponder a better path to the effects I wanted. The essential idea of surface weaving came to me: stitch among a web of loose stitches on the surface, not into and out of a tightly woven base fabric. When I experimented, it worked better than I’d imagined, and that was that.

Tell us more about your “surface weaving” technique. How did it evolve, and what makes it distinct?

I cobbled this method together by taking lessons from several needlework techniques: surface design, applique, machine sewing, hand stitching, couching, and needle-weaving.

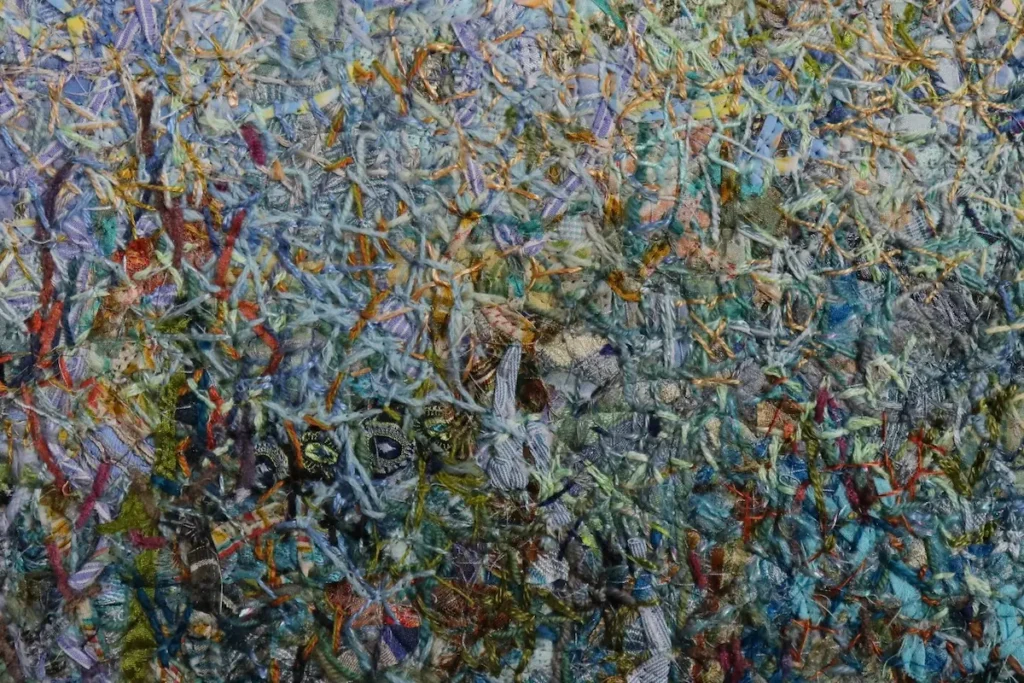

The process starts with a cotton base fabric onto which I paint, print, or appliqué a rough study of the image. By machine, I then free-motion sew large, loose stitches all over the image, forming a thready, random web on the surface. By hand, I then needle-weave string, yarn, and strips of fabric among these stitches until they form a densely woven image over the original study.

This hand weaving stage takes several days to several months, depending on the size. The image develops the way a drawing does, a mark at a time.

When I’m done, I add batting and backing behind the weaving, and free-motion quilt the piece following whichever paths best refine and stabilize the hand-worked image.

The final effect is tapestry-like, but without the pixelated quality of traditional loom weaving. Instead, each strand can start anywhere on the surface, and go off in any direction, for any distance.

Surface weaving is also similar to embroidery as it makes marks with stitches, but it differs from embroidery in that the stitches wind their way over the surface rather than through the base fabric.

Can you share a moment when creating a piece felt transformative, for you or your viewers?

As you can imagine, this technique is time-consuming.

You might think that to make more pieces, I should make smaller pieces. But both productivity and creativity have evolved the most by doing the opposite: attempting pieces larger than I thought I could reasonably handle.

Large pieces speak compellingly and give the creatures more of the power I’d like them to project. For the largest ones, I chose vultures, ostriches, cows – not the most popularly beloved of my usual subjects — and had to push the composition and mark-making to do them justice.

Wrangling with the pieces as large objects also led me to invent better techniques for prepping and finishing, more efficient ways of weaving, studio reorganization, and equipment changes to support larger work.

Tell us more about your bird portraits. How did they come about? What was your intent on working on the series?

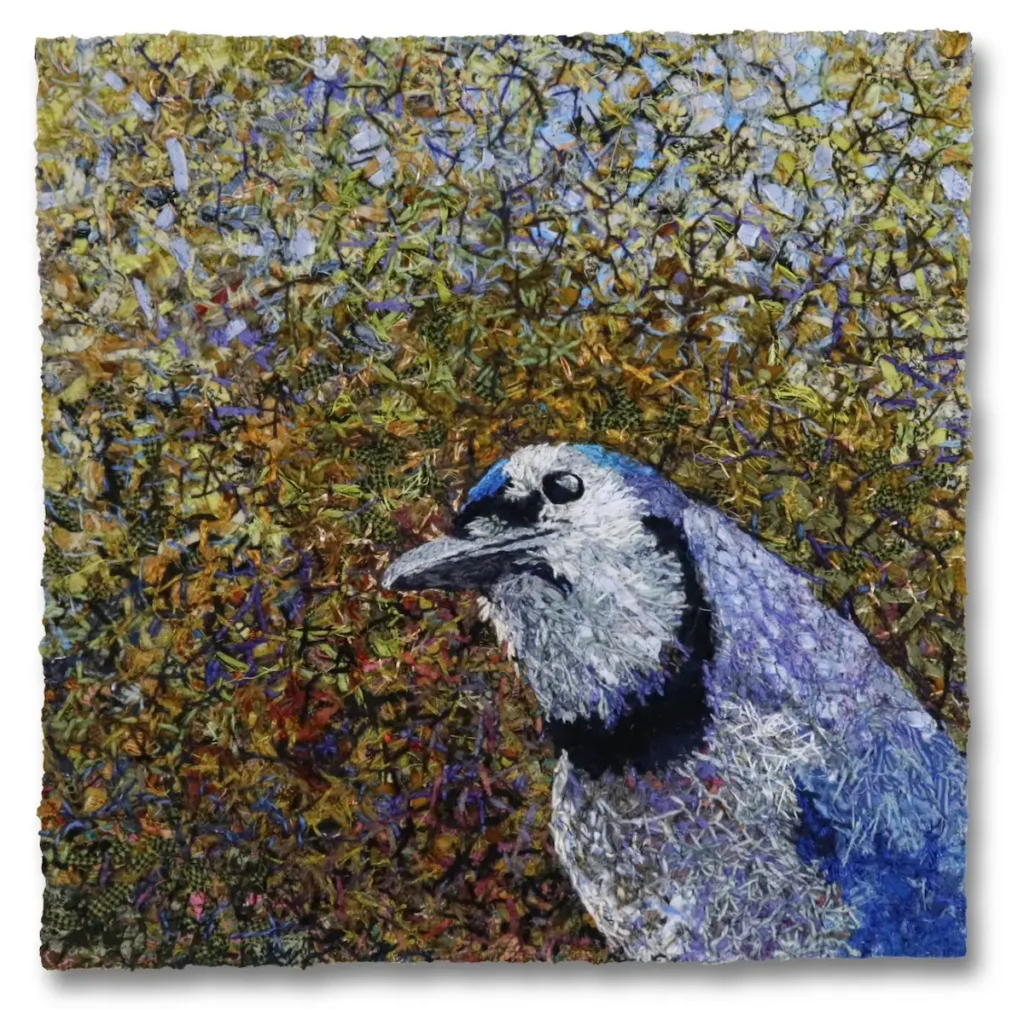

Many people share the experience of paying casual attention to birds, then over time becoming obsessed with them – this is how birders are made. Aside from always loving to see birds and other wildlife, for artistic purposes, I was drawn at first to birds’ beauty, the exquisite design of each species.

I shifted steadily to wanting to capture moments instead of birds – something of the momentary human experience of encountering a bird. This includes our delight at the connection with a wild being, but with keen awareness of the bird’s own power to make and break that thread.

The pieces are realistic in the sense of showing a recognizable bird. But it’s also unrealistic for a bird to be so still, close to you, and gazing directly eye to eye.

I want it to feel intimate and a bit mesmerizing, with more space to feel the feelings: love, personal meanings, maybe an urge to protect, and curiosity for the mysterious goings-on in this other mind.

I also want the pieces to affirm the bird’s wild agency, and again, to create space for our own feelings about this – joy, intrigue, wistfulness, etc.

The bird’s head is most often at roughly human scale, giving it a presence and power on par with the viewer. Its posture and the composition often suggest it could leave at any moment. Often, the bird is only partly visible, and some have their eyes closed or are walking away.

I try to avoid ornithological art customs for illustrating birds as instances of their species. Could we see a cardinal without thinking the label “cardinal”, the way we see people without thinking “humans”?

Making these pieces consumes time to the degree that time is the primary thing some people see in the pieces.

Time serves as part of the medium – people see that the artwork is made of fibre plus lots and lots of time. The effect is like casting a statue in gold instead of bronze – why pour all that value into this image, this idea?

For me, it’s a form of advocacy, and I think it is too for collectors and galleries who show the work.

When do you know a piece is done?

The portraits are never finished before I have sort of a visceral feeling that I’m in the presence of someone and not just a picture.

I always feel that tipping point clearly, but can’t explain it beyond that. If I do continue working on the image, I have to be careful not to kill that sensation.

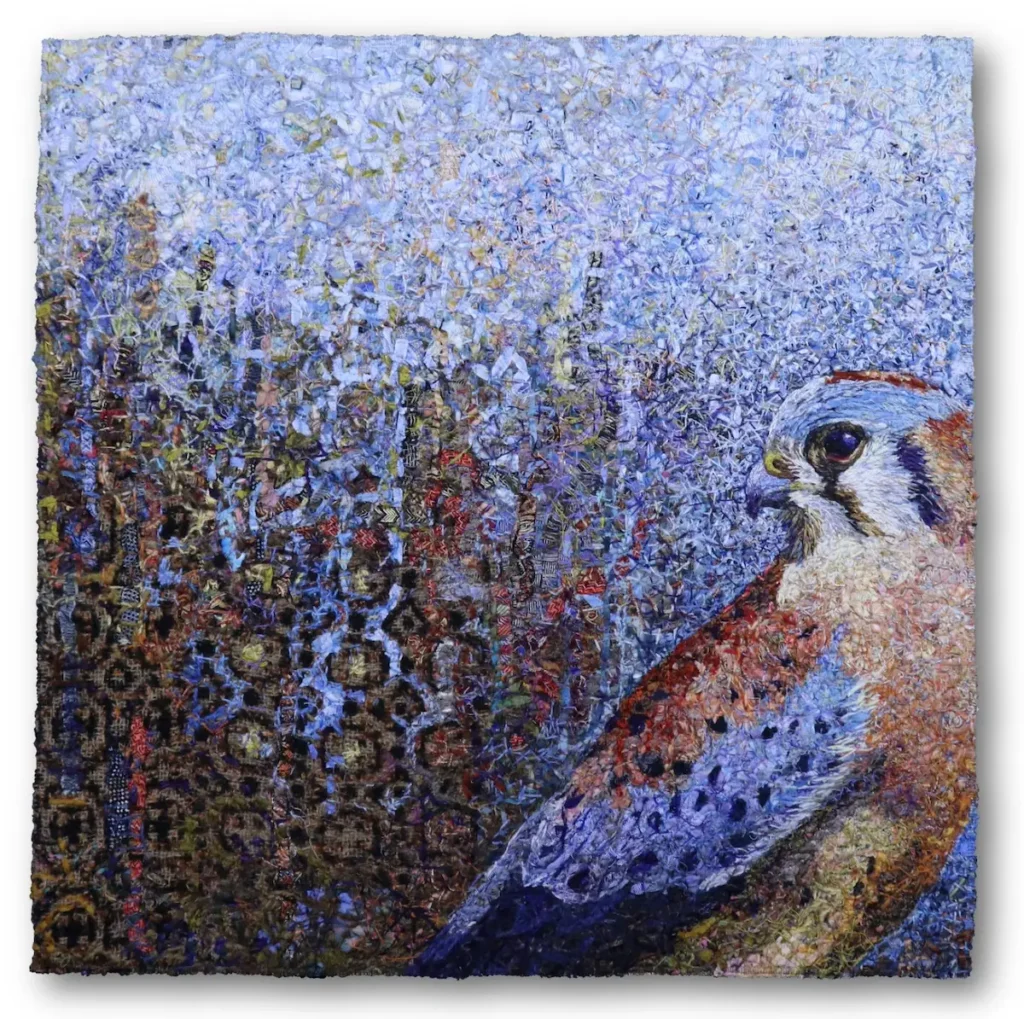

Also, a finished piece must strike the right balance between the visual interest of the whole and the details. Some of the materials have powerful voices of their own, and they need to make a sort of poetic sense in relation to the rest.

The piece “As Above” is a good example of this, where a visible vintage tweed pattern is balanced by the vividly marked kestrel.

How do you stay inspired through the regular ebbs and flows of creative energy?

Making the pieces is the last step in a long process that begins with hundreds (actually, thousands now) of observations, photos, drawings, notes and ideas, gathered whenever they come to me around the clock.

From a handful of these, I work up studies, then choose very few studies to develop into surface weavings. So, every year there are several hundred potential images to distill into a couple of dozen surface weavings. That stream never runs dry because of the vast reservoir feeding it. If anything, it keeps me feeling a bit impatient to create more pieces and realize more of the ideas.

It’s important for me to work in the studio daily, persistently, in all moods and at all energy levels. There is always something constructive to do, even it if it’s just sweeping the lint off the floor.

Beyond the steady studio practice, enjoying nature is my most reliable way to refuel in general. We live in Canada’s most biodiverse zone, so every glance out the window and walk in the woods offers new wonders to feel curious, touched, and excited about.

These days, when I’m not in the studio, I’m busy replacing everything in our garden with native plants and admiring all the visiting wildlife.

What challenges do you have working on intricate pieces? How do you navigate creative fatigue?

The pieces do involve a lot of time and a lot of needlework, but the surface weaving process is more engaging than you might imagine.

Each new stitch involves choosing a new strand from a stash of zillions, and forging its own unique path through the other stitches. Each time, I have to imagine and decide. It’s spontaneous, creative work from one moment to the next, and that’s inherently energizing.

I do need an occasional break from pieces that get overly familiar. They all go through one or more “marination” periods when I put them away to regain perspective while I work on other pieces. I have several in progress at a time, and the rhythm of moving between them helps refresh my eye, too.

What would be your advice for an aspiring fiber artist?

Well, making art is what makes you an artist, so spend as much time as you can working on actual pieces. This applies to any type of art medium, really.

Finish the pieces. Most of them naturally go through messy, unlovable stages – every single one of mine does – but you can’t judge if they’re any good until they’re done.

Finishing things teaches you how to meet your own challenges and improves your mastery over time. And fibre materials really do teach your hands in a direct, intuitive way, the more you handle them.

Where can people see your work?

Website: www.MitaGiacomini.com

I send out email newsletters with exhibit invitations a few times a year. If you’d like to be added to the list, or have any other questions or comments for me, please drop me a note here: https://www.mitagiacomini.com/contact.html. I’ll answer from my email address.

Work is exhibited regularly at:

Carnegie Gallery, Dundas Ontario https://carnegiegallery.org/

Westland Gallery, London Ontario https://westlandgallery.ca

Here are some current SAQA global group exhibits that include my pieces:

Art Evolved: Intertwined

- Suzanne H. Arnold Art Gallery, Annville, Pennsylvania: through December 21, 2025 https://www.saqa.com/art/exhibitions/art-evolved-intertwined-saqa-global-exhibition

- Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, Laurel, Mississippi: January 27, 2026 – April 26, 2026

Aviary

- International Museum of Art & Science, McAllen , Texas: March 21 – June 21, 2026

- Longmont Museum, Longmont, Colorado: January 20 – September 26, 2027

Minimalism

- Mid-Atlantic Quilt Festival – Hampton, Virginia: February 26 – March 1, 2026

- Pennsylvania National Quilt Extravaganza – Oaks, Pennsylvania: September 17 – 20, 2026

Interview posted December 2025

Browse through more inspiring fiber art on Create Whimsy.