Carla Stehr’s creative path winds from tide pools and microscopes to fabric and thread. In this interview, she shares how a career in marine biology shaped her eye for detail and led her to use the sewing machine as a drawing tool, translating microscopic sea life into richly textured fiber art.

Tell us how your creative story began.

Growing up, I thought artists instinctively knew how to draw, and grade school convinced me I couldn’t draw. So, art was not on my radar. But I liked making things, and in 6th grade, my parents signed me up for sewing lessons. I sewed most of my own clothes through high school because at that time, fabric was more affordable than new clothes.

My childhood home had a field, woods, and beach access to Puget Sound. I loved being outdoors and finding things with interesting textures and colors, like lichens on trees and tiny shore crabs or patterned clam shells on the beach. The beauty of marine life and my curiosity about how they lived inspired me to take science classes and become a marine biologist. A couple of college biology classes required students to draw their observations. I struggled with drawing at first, but it gradually got easier. I found that drawing for science requires looking closely, and I loved the process of noticing details.

After college, I was fortunate to get a job in the Electron Microscopy lab at NOAA, Northwest Fisheries. Part of my work included using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) to look at plankton samples and cells and tissues of fish.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Read more about our affiliate linking policy.

The SEM uses electrons to view the surfaces of objects. Electrons allow higher magnifications than what can be seen with light microscopes. Many of the samples I saw as part of research had stunning microscopic patterns when observed with high magnification. That inspired me to explore art.

I read the book Drawing with the Right Side of the Brain, and after completing the exercises, I was astonished to find that I could draw! I now believe that with guidance on “how to see”, anyone can draw. That gave me the confidence to take scientific illustration and other art classes.

Shortly after that, I learned I was going to be an aunt, so I dusted off my sewing machine, got an instruction book, and sewed my first quilt. I found that I didn’t like matching seams for piecing, but I loved the tactile qualities of fabric.

I took a few quilting classes, and it dawned on me during a free-motion stitching class that the sewing machine could be used to draw! That inspired me to experiment with fabric and thread, which quickly became my favorite art materials. I often include hand-dyed fabric, paint, ink, colored pencils, embellishments, and more.

How does marine biology and your scientific work with microscopes influence your art?

I have been passionate about marine life since childhood, so marine biology probably influences my art in ways I am not even aware of. It influences my choice of subjects and how I present them because I want my work to be relatively realistic. I often include information that I learned as a scientist or as a child at heart, wandering tide pools.

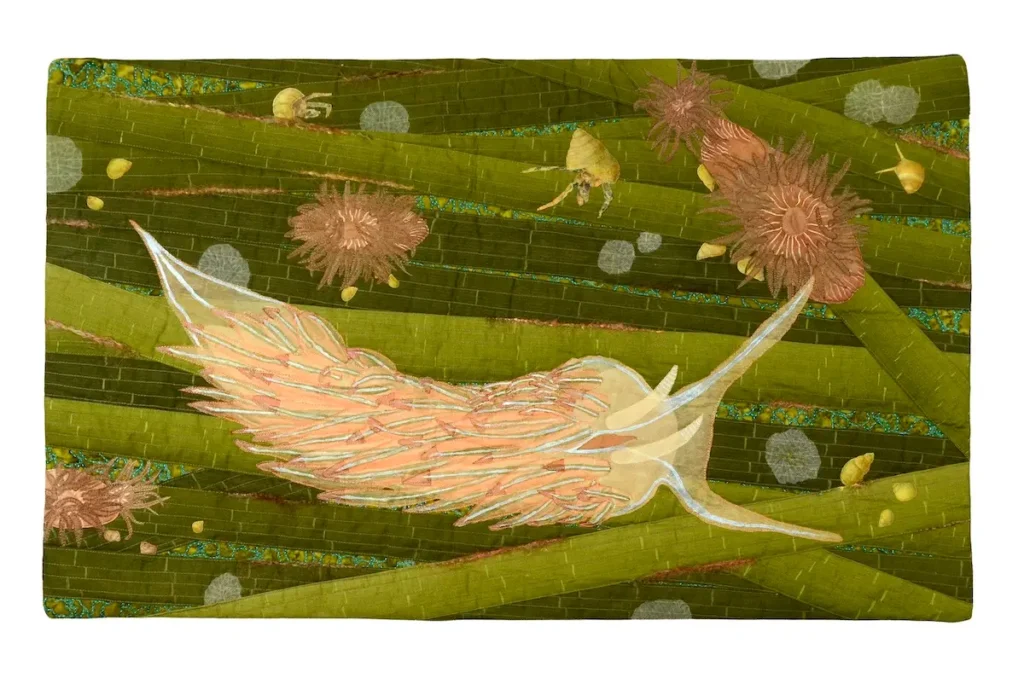

My early pieces were seascapes. Kelp Forest is an example. I wanted to show colorful creatures that live among the kelp in Pacific Northwest marine waters near where I live, including the blue and yellow China rockfish. I soon found, however, that I was most inspired by smaller sea creatures that are not easy to see, such as small anemones and nudibranchs.

The SEM images I photographed as part of science were primarily stored as visual data and sometimes published in scientific papers.

A few years before I retired from science, my colleagues and I saw how the art of these scientific images inspired people to learn more about the marine environment. Several of my SEM images were included in educational publications and exhibits.

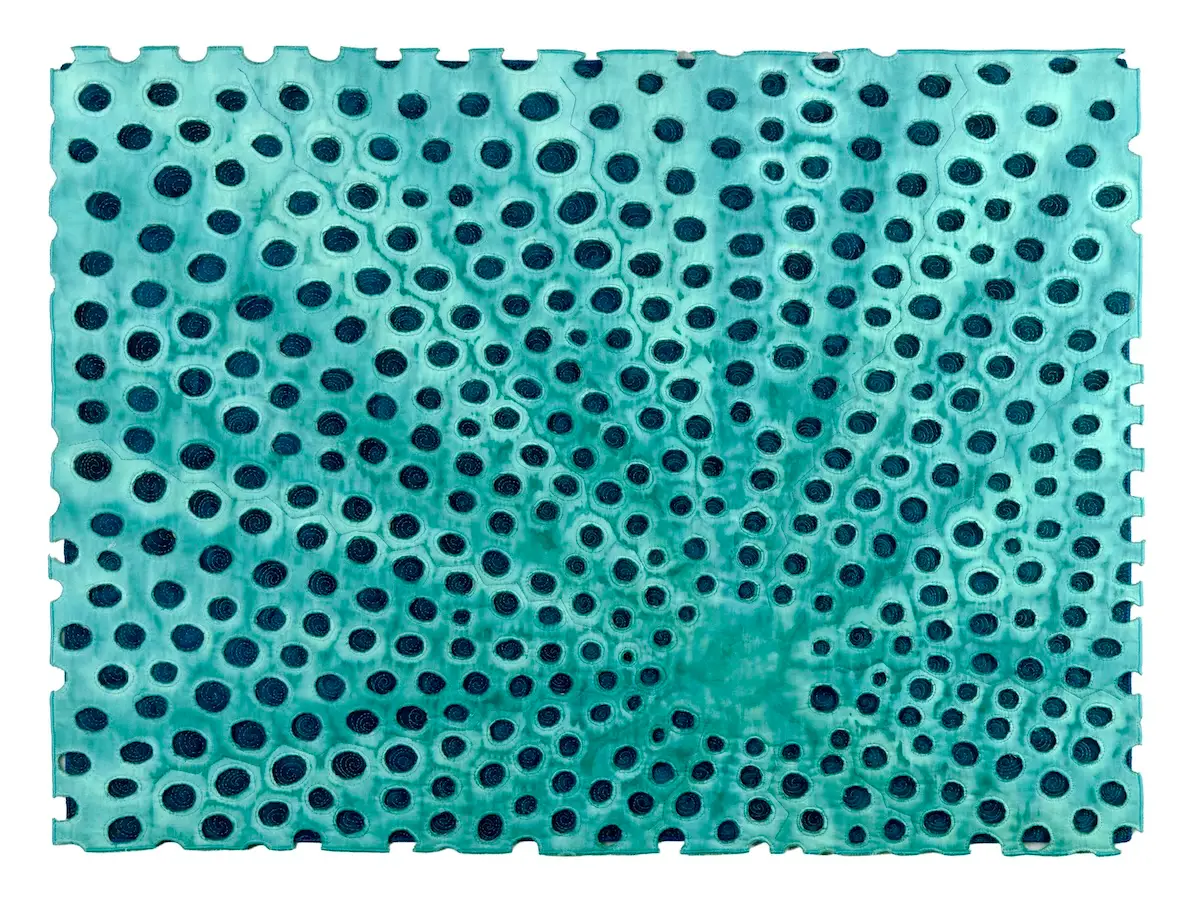

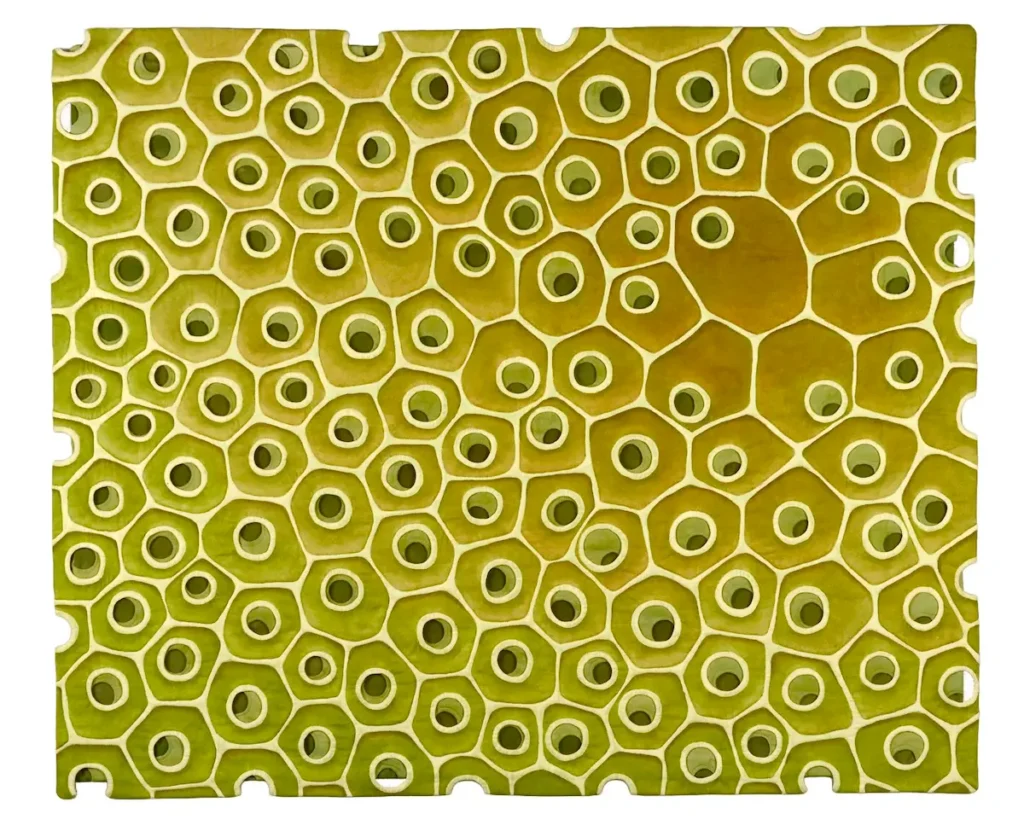

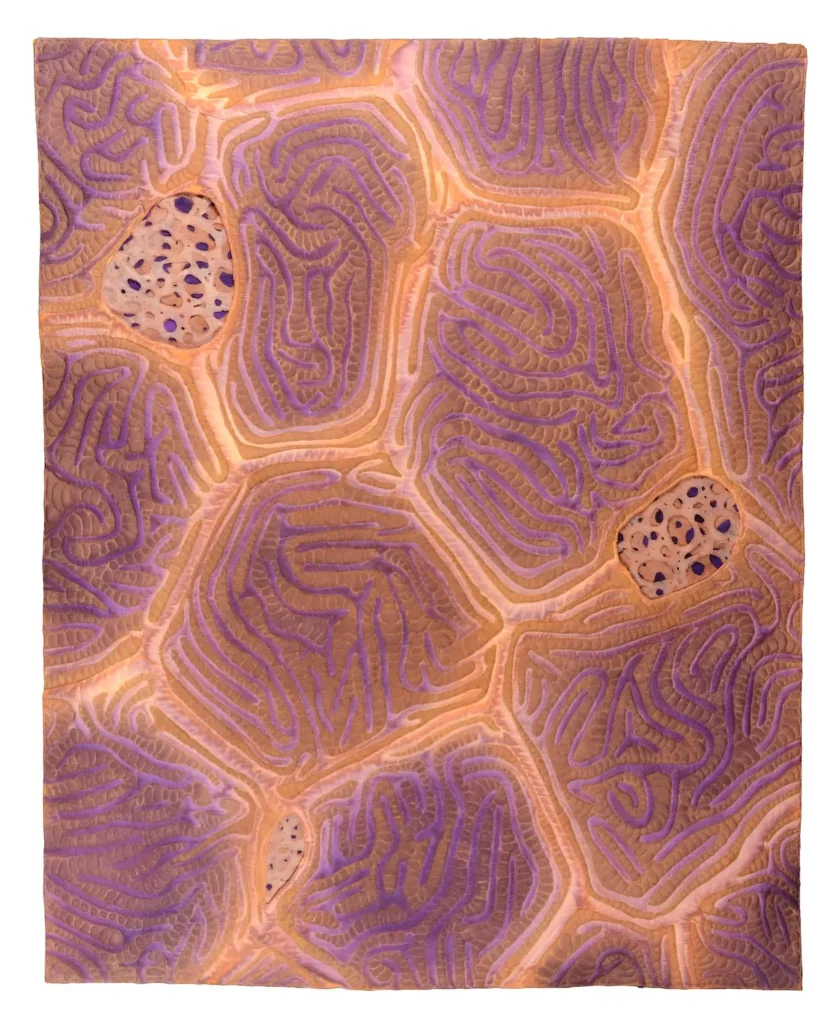

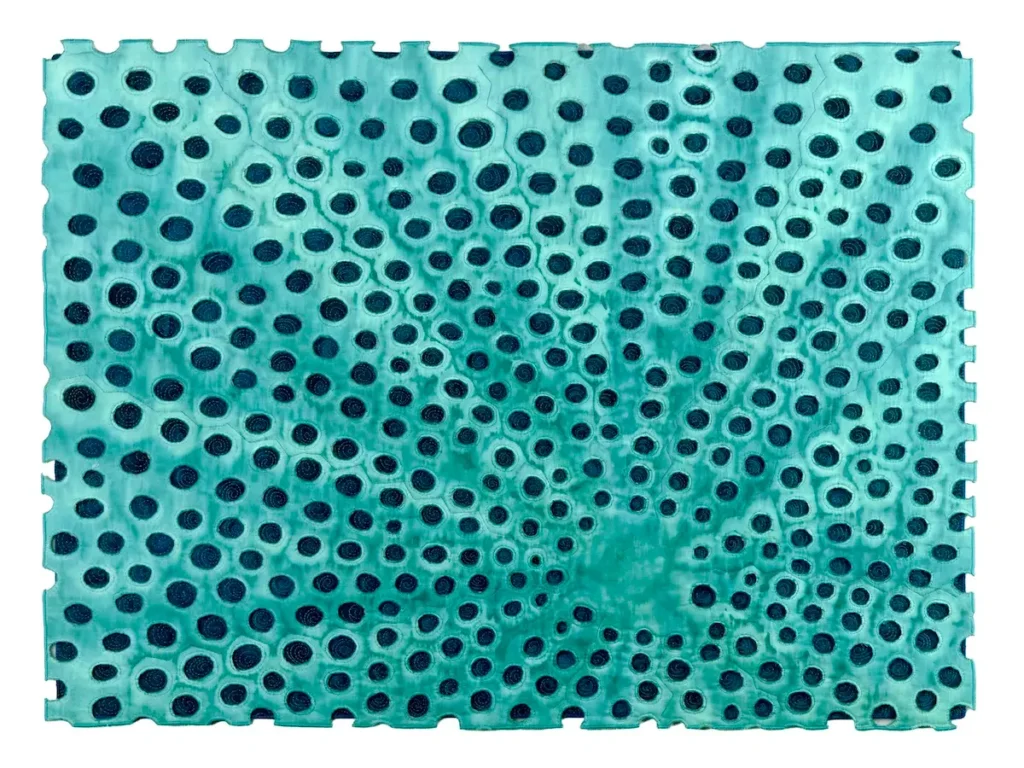

At the same time, I was considering taking a more abstract approach to my fiber art. Recognizing the science and art connection of the SEM images motivated me to use the natural, abstract-like microscopic patterns as inspiration. Examples of my fiber art based on microscopic surface patterns include diatoms and fish skin cells.

A lot of your art is inspired by the sea and tide pools. What is it about the ocean that speaks to you?

I find the variety and colors of sea life to be awe inspiring.

For instance, anemones have beautiful, delicate-looking tentacles, yet they thrive in harsh environments of crashing waves and exposure to extreme temperatures at low tides.

It’s amazing that clams and snails can build hard shells that are often exquisite. Diatoms are single-celled algae that are vitally important because they produce much of the world’s oxygen. It’s incredible that a single cell can be an entire complex organism that is also stunningly beautiful!

How do you decide what techniques and materials to use for a piece?

I try to identify the one or two most important things I want communicate and then experiment with potential approaches.

For instance, I wanted to show that moonglow anemone tentacles are translucent. I experimented with sheer fabrics and found that silk organza backed with Misty Fuse worked great. But silk organza can fray, so I am now experimenting with translucent non-woven fabrics.

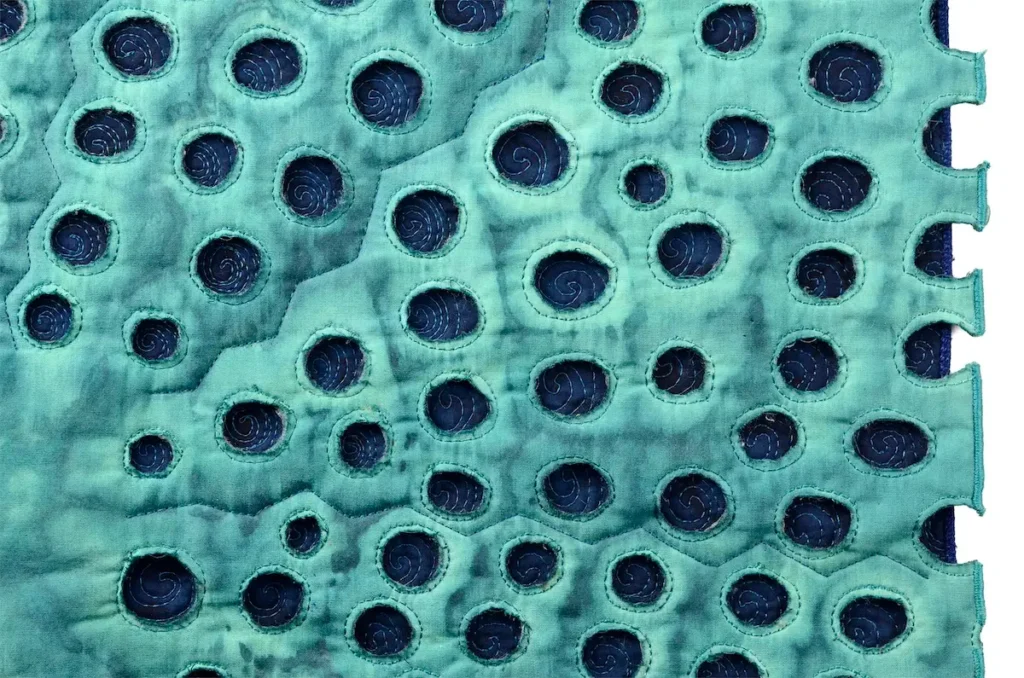

For diatoms, I want to show that even though they are single cells, they have complex, multi-layered cell walls, and each layer has some thickness. I found that fabric stitched to felt gave the surface layer the thickness I was looking for.

Many of my diatom pieces have at least 2 separately quilted layers, where the lower layer can be seen within openings of the top layer.

For my fish skin pieces, I wanted to show specialized cells that make fish slime and how they lie below the skin surface. I adapted techniques from the diatom pieces and cut openings through the entire “skin” quilted surface, then underlined the openings with a contrasting texture of Lutradur to suggest that there is more going on under the surface of the skin.

When a new idea pops into your head, what’s the first thing you do?

My first step is research. It helps me decide if my idea might work, and what features to include or leave out. My ideas often come from my own photos or observations, but I will also study images online to get different perspectives.

For a tidepool animal, I will look up how big it gets, what environment it lives in, its life history, and what it eats. Some of that information may be incorporated into the piece.

For example, Nudibranch on Eelgrass was inspired by my photograph of an opalescent nudibranch on a rock, but the rock wasn’t a very interesting background. I knew this nudibranch also lived on eelgrass, so I looked at my own eelgrass images as well as those online. I learned that this nudibranch eats bryozoans. I remembered seeing small brown anemones on eelgrass, so I researched those. The research helped me decide to give the nudibranch a home on eelgrass and include proliferating anemones, tiny hermit crabs, and bryozoans so that the nudibranch had something to eat.

Can you share a time when something didn’t go as planned and what you learned?

One of my early diatom pieces (Diatom 2) had two quilted layers; the top layer had a lot of stitching around numerous circular openings. I thought the final stitching joining the two layers would add the interest it needed, but it didn’t.

My only idea for a fix was to add paint, but I had not painted over stitching before, and I was afraid it would make things worse. Since I was about to put it in my “didn’t work” bin anyway, I decided I might as well experiment. I got the entire surface wet and applied diluted paint in radiating lines.

I did not like the wet, freshly painted surface, but as it dried, a fascinating pattern developed where the paint pigment migrated to the high spots between the stitching. It added a complexity I never could have imagined. Since then, I have used this technique in a few other pieces. It’s somewhat unpredictable, but it taught me to be more comfortable with the unexpected.

I now consider all my pieces experiments because it frees me to play more, and if it doesn’t turn out, I’ve still learned something.

What inspired you to make three-dimensional pieces?

My first work with dimensional structures were my Denticle pieces. They are based on an SEM image of the skin of the Pacific Spiny dogfish shark.

Shark skin is covered with microscopic, hard, tooth-like structures called denticles. I am fascinated by the dimensional qualities of the denticles and how they grow from underneath the skin. After a lot of experiments, I covered stiff interfacing with fabric to create the denticles, then partially pushed them through openings in the underlying quilted “skin”. Making the denticles inspired me to explore other dimensional structures. I made barnacles from thick paper called Kraftex and stitched them onto a 2D piece made to resemble an oyster.

Making that piece got me wondering about making a 3D oyster where both sides of the shell could be seen. After many more experiments, I used wireform mesh sandwiched between layers of felt and fabric to make the piece dimensional. One thing often leads to another!

Where can people see your work?

You can see my work on my website: https://carlastehr.com/

Interview posted January 2026

Browse through more fiber art inspiration on Create Whimsy.