Joe Cunningham was planted in the quilt world when he leaped at an opportunity to collaborate on a project to chronicle the life and work of quilter Mary Schafer. In his growing appreciation for the art form and the women who created it, Joe has become an accomplished quilt artist, creating artistic paths of his own while honoring the traditions of the past.

What was your path to quiltmaking?

Growing up on a dirt road in Michigan, I felt that the worlds of art and culture that I read about in books were off limits to me. I did finally learn that, while I had no talent for making art myself, I could still get close to it and study it by going to museums, reading criticism and studying biographies of artists. Once I started making my living by playing guitar I had my own art form anyway.

But I always wanted to write. When I was 25 I took a job teaching guitar at a small college in Colorado so my salary would offset my tuition and books. The next summer, 1979, I went back to my home town, Flint, and found myself playing in some of the old nightclubs. One night, a woman named Gwen Marston introduced herself to me in between sets, and asked if I would be available to play guitar on some of her folk music gigs. Over at her house for rehearsals I saw boxes of interesting looking things that turned out to be quilts. Gwen had gotten a grant to document another woman’s quilt collection and archive: Mary Schafer. Gwen was enjoying the process of gathering all the information on the quilts but she was dreading the writing of the catalogue, a project that would include a short biography of Mary.

Having studied English for a year I felt eminently qualified to write it for her, and I volunteered. She said, “If you were going to write about quilts you would have to know something about quilts.” I knew that she had all 5 or 6 books with any scholarly content on the subject, and I said I would read them all.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Read more about our affiliate linking policy.

Then I met Mary, who thought that being a quilt maker meant that you had to learn quilt history, textile history, quilt design and engineering, and artistry to put it all together. One night Gwen came over to my apartment with a small quilt in a hoop and a big thimble. “If you are going to write about quilts,” she said, “You should know how to quilt. Here is the rocking stitch.” By the time I finished that small quilt I could quilt well enough to sit at Gwen’s frame and quilt with her.

Within a few months, I figured out that, if we were going to find a home for Mary’s collection and archive, we would need to become professional quilters ourselves. That way we could use her quilts for lectures and magazine articles, maybe even books if we could be lucky enough to get a book contract. Eventually we could get enough credibility in the quilt world that we could leverage it into finding an institution that would take charge of Mary’s collection and preserve it.

Along the way, I started wanting to make my own quilts. Gwen and I ended up making many quilts together, writing books on the subject and traveling all over the country to teach. We worked together all through the 1980’s. In the early 1990’s I moved to New York City, then to Vermont and eventually to San Francisco to work with the ESPRIT clothing company’s quilt collection. In San Francisco I got married, had two sons and started working on my own solo work. I have been there ever since.

At some point I realized that I had turned into an artist, without meaning to. I saw that my quiltmaking had turned into art making, and that I had become an artist through the side door, as it were.

As a man in a field traditionally viewed as “women’s work”, how difficult was it to be taken seriously as a quiltmaker?

It was not difficult. My experience has been the very opposite of a typical woman’s experience when she enters a men’s realm. Men, often, do anything they can think of to keep a woman down, in the military, in the police force, in construction, in business. In my experience, I was not only welcomed into the quilt world, I was treated with respect from the very beginning. Eventually I became a quilter like any other, one who had to make high quality work to stay afloat. But at first they always gave the benefit of the doubt.

How long did you work with the Gee’s Bend women? How did that opportunity come about, and what did you learn from the experience?

I became aware of them when they had their first big show at the Houston Museum. My friend Julie Silber got a private tour of the show and called me from the galleries, saying “You have got to see these quilts, you will love them.”

A few years later the women came to San Francisco, where one of their stops was to visit my studio. We ended up being friends almost instantly. I ended up going to church with them, going to dinner with them, and being invited to come and visit them in Gee’s Bend.

In 2009, Julie Silber told me she wanted to go to Gee’s Bend for her 65th birthday with me for a week, a project for which I wrote and received a grant. There, I just sat down at the frame with Lucy Mingo and Lola, imitated their stitches and started following their lines. Eventually I met a number of the women and had a great time quilting all week and visiting. The next year I had a lecture tour in Louisiana. I decided to extend it long enough to go back to Selma and Gee’s Bend for a few days. A couple years later, the producer of Craft in America asked to feature me. And what would I like to do? I told her I wanted to meet the video crew both in Gee’s Bend and in my San Francisco studio.

Since then I have stayed in touch with Lucy and with Rita Mae Pettway by phone and mail.

What I learned was that a 19th century way of quiltmaking was still possible. By that I mean that the freedom of thought coupled with a simple mastery of technique could allow one to make quilts in a simple, direct way, quilts that could exist both as blankets and as works of art simultaneously.

Tell us about your artist-in-residence experience at the De Young Museum. How did that come about, and what was a typical day like, if there was any such thing?

The DeYoung had just bought one of my quilts, so I was on their radar. Somehow I heard about their residency program and learned that I could apply for it. The idea was to be able to occupy their education studio for one month with an exhibition of your work and projects for the public to interact with. So I proposed a wall of felt and boxes of fabric scraps be made available, where people could create their own fabric compositions, which one of my interns could photograph. We printed out two copies, one for the person to take with them and one to put on our wall.

I also had a frame set up where I could teach people how to quilt. I had my own sewing machine so I could make quilt tops. And I had my guitar with me, so I could play a tune here and there and so musicians could come in and jam once in a while. School groups came by, which I would show around and teach a little quilt history. I had four interns to help with everything, and I got paid for the privilege. All in all it was one of the greatest times of my life. I recently learned the De Young Museum discontinued the program. I don’t know why.

How do the quilts you make today differ from the quilts you made when you started quiltmaking?

I started by copying old quilts and imitating old quilt styles. Under Mary Schafer’s direction, that was my form of “quilt college”. By copying old quilts stitch for stitch I hoped to find the feeling that the old time quiltmakers had. As the years passed, I continued to work in what I thought of as a neoclassical style. I wanted to demonstrate that you could work in the old ways and be completely original at the same time. I thought that in that way I was honoring the women of the past, whom I revered.

Eventually I came to the realization that if I wanted to honor them, what I should do is what they actually did; they were not honoring a tradition in the 19th century, they were blowing one up! American women of the 19th century created a realm of total artistic freedom where we could sew anything together any way we wanted. That was the part of the tradition I should follow, I decided, and I should follow it by making whatever I could conceive and believe in.

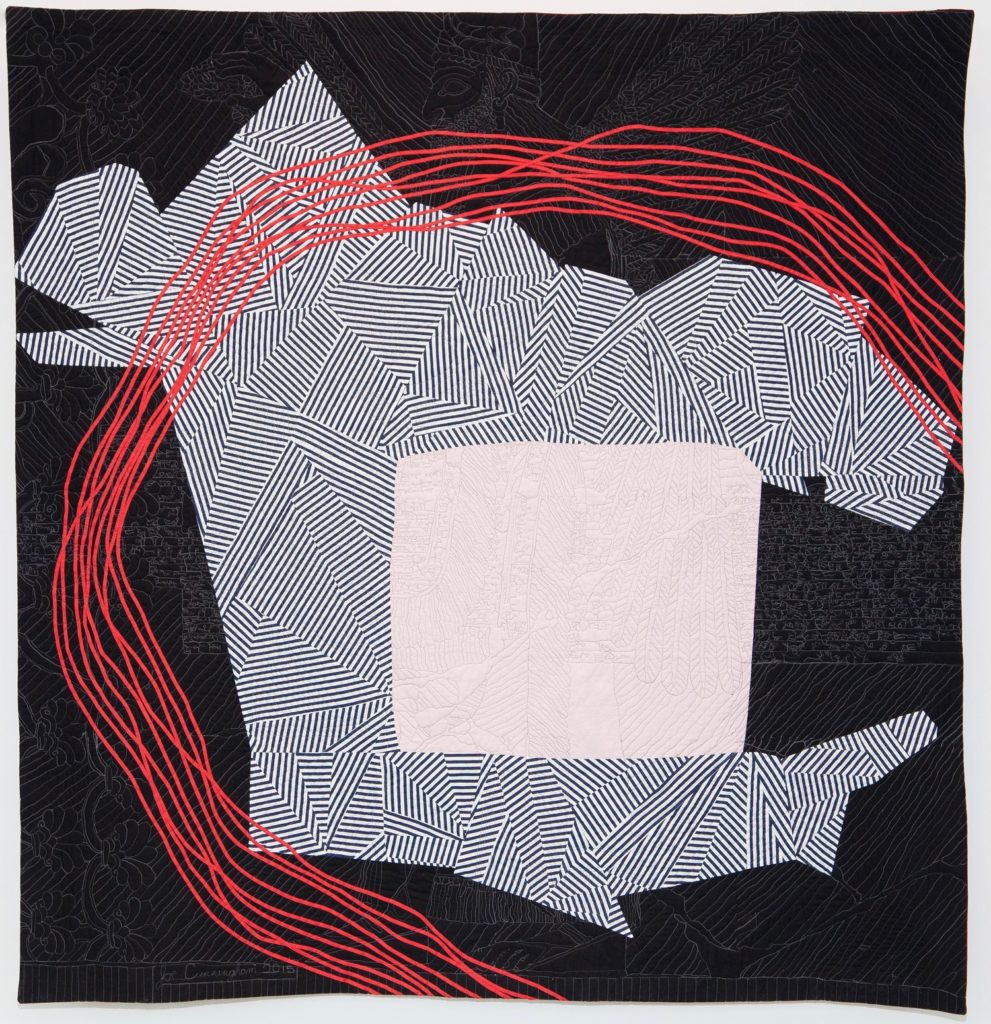

So in simple terms, I started out using traditional forms, such as medallions, or block styles, with borders and bindings. Now I do large, single image quilts with no borders and with facings instead of bindings.

What inspires you? Are there recurring themes in your work?

I walk a lot, and I get a lot of inspiration for my work from observing nature. Also, ecological issues seem to crop up all the time. I am working now on a series of quilts about the end of the last Ice Age, 12,500 years ago, when glaciers were melting and many animals were going extinct.

When you begin to create, do you visualize the finished piece? Or does the work evolve?

I always start with a theme for the quilt. I know what I am making before I start sewing. And I know that it is going to be about six feet square. Then I pick out a bunch of fabrics that might work for me, for this vague image I have in mind that will convey the theme. Any fabrics that look like they go together go back on the shelf. Then, as I start cutting and sewing and putting bits on my design wall, the piece begins to take on a life of its own. Sometimes it ends up completely different than I imagined it.

Techniques? What do you do differently? What is your signature that makes your work stand out as yours?

I use simple techniques, nothing special for the most part. 15 years ago, I started using bias tape for graffiti-like lines, something which is a sort of signature of mine. I simply top stitch it down freehand on both edges with matching thread. With my computerized Handi Quilter longarm machine I do a lot of detailed transcriptions of photographs, blueprints and other unusual imagery. For instance, on my latest quilt, “Monument to Discarded Love,” I drew a couple piles of smashed cars and old tires from a junkyard.

Tell us about a challenging piece. What were the obstacles and how did you get past them?

A developer recently commissioned me to do a large piece for a 20’ concrete wall. We decided it should be about a 9’ square quilt, and he wanted only abstract design. The challenge: I had to draw it out and get design approval before I started sewing. Also, they needed to approve the actual fabrics I would use. It was the opposite of the way I usually work. But they were spending a lot of money. Understandably, they wanted to know what they were going to get for it.

After they rejected my third design proposal, I began to fret. Finally, the consultant who hired me in explained that clients like options…like graphic designers had given me in the past. “Here is your logo in three different color ways—pick one and left me know.” So I came up with a design where I could move one of the major elements around. Then I gave them three different options for placement. Also, I created a theme for it which could have a solid metaphorical intent. “Another Way Home” lent itself to a story for the piece that we both liked.

Once the client picked Option C, I could start work. I realized that if I were to do more of this kind of work I would have to be open to the possibility that sometimes the client could be right about an artistic decision. Otherwise I would be full of resentment and misery. In the end, I loved making it and I loved the piece.

What is the last artwork you purchased?

I recently traded a large quilt for a large drawing by my friend Heike Liss. She listens to music and responds with lines on vellum. Sort of in the realm of Cy Twombly. But totally her own thing. I love it.

Do you think that creativity comes naturally to people? Or do you think creativity is a skill that people can learn?

I do not think it comes naturally to all people to be creative in an artistic way. An element of our culture is specialization, which does not foster the idea that we are all creative people. Instead, we learn early that we are good at some things and not at others. Given the fact that we are indeed born with certain strengths and weaknesses, you can see how this idea developed.

Nevertheless, I believe that creativity is a skill that anyone can learn. After all, I could learn to ski without much of an athletic background, a lousy sense of balance and a weak kinetic sense. All I had to do was to be willing to try and to get up every time I fell. I never achieved a high level of skill, but I did get so I could enjoy gliding down the mountain. In the same way, anyone can learn to be artistically creative if they are willing to try. And then get up when they fall.

You take on some big guns in the creative world – fashion designers and artists who use completed quilts as little more than uncredited raw material for their own work. Would you step up on your soapbox for a moment and share your opinion of the practice?

Here is the problem with this sort of practice. In our society we do not value women, and especially old women. There is no worse thing you can say to a person than they do something “like an old lady”. In a million ways we ridicule and diminish older women like no other group of people. Quilts are objects in our culture that have old ladyness built into their DNA. So much that quilters and everyone who writes about them love to point out, “This is NOT your grandmother’s quilt!” The implication is that there is something boring or stupid or terrible about your grandmother’s quilt. The premise is always that these musty old things from times past have no value. Not until people younger and smarter than your grandmother update, repurpose and recontextualize them.

All of this is to deny the monumental creative achievements of the 19th century American quiltmakers. They created a realm of infinite visual possibility for us all. Inventing whole ways of thinking and making that would only be “discovered” by artists of the 20th century, they came up with the idea that unrelated materials could be slammed together side by side in ways that were not done in painting, in literature, in music or any art form until much later. Think of Charles Ives around the turn of the century or John Cage later.

Quilters were making six or seven foot square abstract compositions in the middle of the 1800’s. They quilted an often foreign grid right across the pieced or appliquéd design, sort of like Robert Longo and other painters of the 1970’s would begin to layer unrelated lines and images on their paintings, or, if you wanted to go back further, you could find Bauhaus artists maybe drawing lines across other imagery in the earlier part of the century. But quilters did all this first. They developed a conceptual framework where they could have complete creative freedom.

Because it was complete creative freedom for ordinary women to make blankets for the home, it was never taken seriously by the academy, by critics or commentators on art. After all, how could something made by little old ladies be revolutionary or interesting or valuable?

It follows that when a designer or artist finds an old quilt they want to use, they always have to make sure to tell us that they are “honoring” it by using it in their own work, a use I feel is just a cheating way to get the feel of “authenticity”, of bringing something real and true into their work without the trouble of actually doing something real and true. It is what people say about it that bothers me. When Rauschenberg nailed a quilt to a piece of plywood and painted and drew on it, he did not claim to be honoring it. He was making art and he did not need to justify or diminish the quilt to prove how superior he was. But commentators have often talked about how he elevated this humble domestic object into the world of art thereby.

To sum up, I feel the collective genius of the 19th century quiltmakers has never been adequately recognized and has in fact been denied in our culture. The brilliant quilts they made are so little valued that they can be cut up and “repurposed” at will and in great numbers. How about cutting up and repurposing 19th century paintings instead?

Tell us about your studio set up.

I have a library of quilt and art books I study all the time for inspiration. I cut on a large table and sew with a Bernina 130. My eight-foot square design wall is black on one side and white on the other, so I can use whichever side is best for my current project. I quilt either by hand on an old fashioned frame, or on my computerized Handi Quilter Fusion. I press with my Laura Star steam iron. These things are all indispensable to me and they make it possible for me to create freely.

What plays in the background while you work? Silence? Music, audiobooks, movies? What kind?

Usually I like to work in silence. Sometimes I play music of any kind I like at the moment…usually rock and pop music, but sometimes classical or indigenous. A couple weeks ago I picked up Petra Haden’s a cappella version of The Who Sell Out and have listened to it a few times. I listen to NPR sometimes. Wilco. Bartok. Mance Lipscomb.

When you travel to teach workshops, do you stitch on planes, trains and automobiles and in waiting areas?

Nope. I read.

What is in your creative travel kit?

My iPad so I can catch up on the things I am supposed to be writing, like this. And I always have my guitar to write with and to play in my hotel room.

What is on your design wall right now?

Nothing! I just finished a quilt and brought it with me on this trip to Australia. Until I sew the facing down by hand and apply the hanging sleeve, I won’t start another project. I always work on one piece start to finish, then clean up my studio and start another one.

Tell us about your blog and/or website. What do you hope people will gain by visiting?

My poor blog sits there ignored while I post clever little things on my facebook pages and my Instagram. While I make videos on my YouTube channel. On YouTube I am making short videos called The Quilt Report. In these I am hoping to talk about whatever is on my mind that week. I just finished #23.

On my website, www.joethequilter.com, I hope to show some of my work, to show my resume and to describe my classes and lectures. I keep my schedule up to date so you can see when I am going to be where.

Do you lecture or teach workshops?

I teach all over all the time.

How can students/organizers get in touch with you to schedule an event?

People can go to my website or write to me and ask to be put on my email list. Write to Joe@joethequilter.com and put “email list” in the subject line. I promise to send out a newsletter soon.

Interview published April, 2019

Browse through all of the quilt artists interviews on Create Whimsy.